WELCOME TO

SARATOGA VOICES

The power of singing

News & Events

-

Mozart’s Requiem with the Schenectady-Saratoga Symphony Orchestra-Night 1 Saturday, Apr 27th, 2024 @ 7:00:pmLearn More

Mozart’s Requiem with the Schenectady-Saratoga Symphony Orchestra-Night 1 Saturday, Apr 27th, 2024 @ 7:00:pmLearn More

Saratoga Voices Announces New Artistic Director Noah Palmer

Saratoga Voices’ Board of Directors is pleased to announce that Noah Palmer will be the chorus’s new Artistic Director. Starting on July 1, 2023, he will be the group’s sixth director in the organization’s 53-year history, including the decades when the chorus was...

MUSIC REVIEW: Saratoga Voices soar in final concert of season

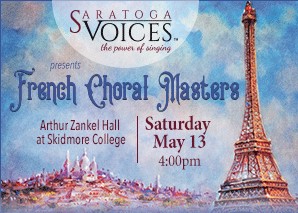

Daily Gazette - MUSIC REVIEW: Saratoga Voices soar in final concert of season By Geraldine Freeman | May 14, 2023 Saratoga Voices gave their last concert of the season Saturday afternoon at Arthur Zankel Hall at Skidmore College with a program of very serious music...

In Remembrance: William Jon Gray

Our former Artistic Director, Dr. William Jon Gray, passed away on Wednesday, July 27, 2022. Bill led the former Burnt Hills Oratorio Society and was integral in the transitioning of the group to become known as Saratoga Voices. During his tenure from 2016-2021, we...

For Over 50 Years

Saratoga Voices embraces the choral arts within a vibrant, collaborative, and skill-nurturing environment, striving for excellence in choral performances, including diverse artists and audiences to share the joy and power of singing.

EXPLORE SARATOGA VOICES

Upcoming Events

Upcoming Events

Our Latest News

Our Latest News

Scholarship Program

Scholarship Program

Advertising Partners

Advertising Partners

Voice Your Support

Voice Your Support

Join Our Chorus

Join Our Chorus

TESTIMONIALS

PROUD MEMBERS

JOIN OUR NEWSLETTER

Stay informed! Subscribe to our mailing list for performance announcements, latest news & more.